A couple of months back I posted a blog about a new New York City-based all-analogue label, Analog Tone Factory. ‘All-analogue’ in the sense that all of the label’s recordings will be captured exclusively on reel-to-reel tape. The resulting albums will then be available in multiple formats including R2R tape (quarter inch, 15ips, IEC/CCIR), AAA 180g vinyl and in various digital formats.

A couple of months back I posted a blog about a new New York City-based all-analogue label, Analog Tone Factory. ‘All-analogue’ in the sense that all of the label’s recordings will be captured exclusively on reel-to-reel tape. The resulting albums will then be available in multiple formats including R2R tape (quarter inch, 15ips, IEC/CCIR), AAA 180g vinyl and in various digital formats.

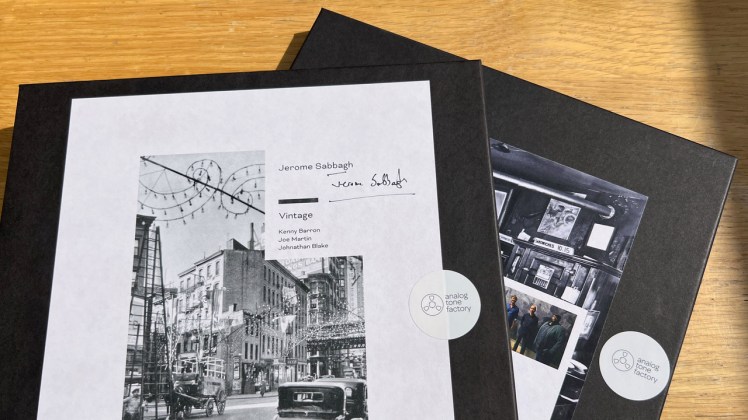

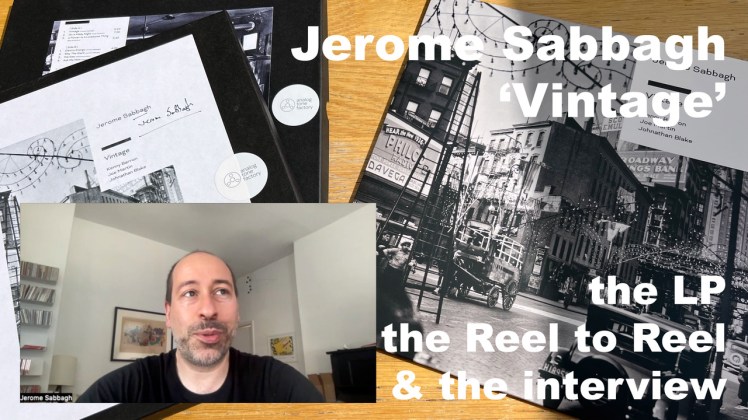

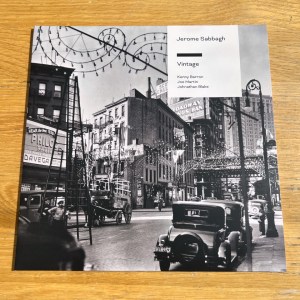

At the label’s helm are audiophile and jazz saxophonist Jerome Sabbagh and pianist and recording / mixing engineer Pete Rende. Early outputs include a trio of jazz albums by Sabbagh himself, and I got hold of a recent release, called ‘Vintage’, for review.

As I mentioned in the previous blog, the album has already had some great reviews, including in the New York City Jazz Review and Hot House, as well as in Michael Fremer’s Tracking Angle and Stereophile (where it was record of the month for February 2024). It was also described as “one of the best jazz albums of 2023” by The Absolute Sound in a recent round-up of audiophile jazz on vinyl – all of which had me keenly anticipating the arrival of my copy!

First up, a few introductions and acknowledgements. The line-up of performers is:

- Jerome Sabbagh – tenor saxophone

- Kenny Barron – piano

- Joe Martin – bass

- Johnathan Blake – drums

Check out the links, there are some impressive credentials here!

And the production credits:

- Recorded by Ryan Streber at Oktaven Audio, Mount Vernon, to multitrack analogue tape on a Studer A800 MKIII at 30ips (November 5, 2020)

- Mixed by Pete Rende at Brooklyn Recording, Brooklyn, on a custom 1/2 -inch tube Ampex 351 at 30ips (November 13-14, 2022)

- Assistant Mixing Engineers: Andy Taub, Samuel Wahl

- Mastered by Bernie Grundman at Bernie Grundman Mastering, Hollywood

- Master lacquer cut by Bernie Grundman directly from the analogue tape, using an all-tube system

- Produced by Jerome Sabbagh

Executive Producer for the vinyl edition: darTZeel

Listening notes track by track

Let’s kick off with the music itself and afterwards then I’ll say a bit more about the experience of listening on tape versus on vinyl, since I have a copy of both here – on very kind loan from Jerome – in order to compare them. (PS. If this isn’t too much of a spoiler alert, I bought the tape after this review as I didn’t want to return it!).

Side 1 / Track 1: Vintage (Jerome Sabbagh)

Side 1 / Track 1: Vintage (Jerome Sabbagh)

Right from the off, this track has an easy going swinging feel that puts me in mind of early 1950s Miles Davis. The sound is warm and soft (in the nicest way), and also organic and natural. The drums, bass, piano and saxophone are all very nicely weighted – no one instrument pushes forwards. When the drum plays solos, the drums stay in their place in the soundstage rather than leaping forward (as can often be the case). During the saxophone solo that follows, the saxophone is warm and gentle, not glassy or glaring. It too remains in the same plane (front to back) within the soundstage. Before the song wraps up, the quartet slips into a Latinesque kind of rumba thing which is pretty delicious!

Side 1 / Track 2: On A Misty Night (Tadd Dameron)

Again, the sax intro feels to me like early 50s (1950-55) Miles Davis, with its a soft and sultry swinging groove. I want to say that that this record doesn’t sound ‘audiophile’ in any way – which is not a bad thing: it sounds authentic, organic and natural, unlike so many so-called audiophile recordings that (to me) can sound somewhat sterile and contrived, like a hyper-detailed micro-reality. The piano solo here just flows, the full gamut of colour is so natural, it’s not stark and it has no signs of ‘digitisis’. As the track progresses I’m acutely aware of the left and right hands of the pianist, and I can intuitively hear and feel and connect with the whole groove. The bass is nicely weighted, the drums are subtle and real, the bass solo has real presence and again, it’s not thrust forward. Every note is defined yet soft; the notes start and stop in a wholly natural way with the full spectrum of colour, depth and feeling. The saxophone, I have to say, is particularly wonderful – it’s kinda reminiscent of Stan Getz on this number.

Side 1 / Track 3: A Flower is a Lovesome Thing (Billy Strayhorn)

Here we have largely saxophone with piano accompaniment. The sound of Sabbagh’s breath during the sax solo is so ‘there’, so in-the-room real, like the man is standing in front of me in the room. But to be clear, it’s not just the sound quality that’s worthy of note here. The touch and feel of the musicians is right up there. Of course this is no bunch of amateurs, what we have here is a gifted ensemble of ‘old hands’ who, between them, bring a massively impressive track record and portfolio of work. They echo bands of the highest echelons, and the way this particular track with piano and saxophone holds together makes this very apparent indeed.

Side 2 / Track 1: Elson’s Energy (Jerome Sabbagh)

A wonderful Latinesque beat and a swinging groove. The drums seem to lead the way on this tune, but with the whole band (from left to right: sax, piano, bass and drums) very much in synch and absolutely swinging along. The drum finale to the song is particularly impressive. Boy, this is one heck of a well-recorded album!

Side 2 / Track 2: Slay the Giant (Jerome Sabbagh)

A slower, more bluesy sax opens this tune, with the whole band swinging slowly. Nothing jars, this veeery easy listening. It’s mood-inducing, calm, peaceful, relaxing. It has a wonderful late-night feel. Bass and piano duet over the drums with an extremely neutral tonality and warmth. It’s quite the anthesis of ‘stark and clinical’, you can hear the ambiance of the studio at Oktavan Audio. It’s very obviously a live performance – it feels so natural.

Side 2 / Track 3: We See (Thelonious Monk)

This Monk composition is very ‘Monky’. Barron (piano) and Sabbagh (sax) do themselves proud. The weight and colour of this duo is sublimely seductive. Every percussive note of the piano is weighty and delivered absolutely on the nail. It sounds very, very natural and is utterly captivating.

Side 2 / Track 4: Ask Me Now (Thelonious Monk)

To end the album, all I can say is that what we have here is sublime tonality, timbre and timing. The three Ts, if you like (is that a thing?!). The essence of great music. This whole album documents a stunning performance, and is a gorgeous recording. It has such a 1950s feel – the tonality and authenticity, yet coupled with a 21st century resolution and fidelity.

A few notes on the vinyl edition

The vinyl edition was pressed at Gotta Groove in Cleveland, a pressing plant which I’m completely unfamiliar with, but based on this example is seems to be right up there with the best. There’s nothing to criticise in the physical media at all.

The vinyl edition was pressed at Gotta Groove in Cleveland, a pressing plant which I’m completely unfamiliar with, but based on this example is seems to be right up there with the best. There’s nothing to criticise in the physical media at all.

I see that there are four versions of this LP record: a standard edition ($40), numbered limited edition of 500 ($55), a signed, numbered edition ($75) and a signed test pressing ($100). I’ve got a standard edition here. I’m not sure how many test pressings there are (at the time of writing there are two test pressings still available) but those are very tempting and, along with the limited / numbered and signed editions, they will no doubt become collectable.

And so to the tape

Obviously there’s another edition that I need to talk about, and that’s the one-to-one, direct, first generation copy of the original master tape. The (introductory) offer price of this is a highly tempting $525.

Anyway, I’ve discussed many times before how a master tape differs from even the very best cut / produced vinyl albums, and I can wholeheartedly report that Vintage is no different…

In fact, it’s quite an eye-opener. Yes, I know I bang on about this A LOT, but seriously folks, the degree of difference never ceases to grab me by the guts and defy expectations. No matter how many times I do this, I’m always left shaking my head, thinking woah, I knew it’d be different – but not this different! The overall openness takes a big step forward. It’s like you’ve removed a couple of net curtains from in front of the performance. The image placement is now set in stone. It’s rock solid, holographic, tangibly tactile. The dynamic range – both in an overall sense and in the subtler micro dynamics that so define the reality of natural sounds – is far superior.

In fact, it’s quite an eye-opener. Yes, I know I bang on about this A LOT, but seriously folks, the degree of difference never ceases to grab me by the guts and defy expectations. No matter how many times I do this, I’m always left shaking my head, thinking woah, I knew it’d be different – but not this different! The overall openness takes a big step forward. It’s like you’ve removed a couple of net curtains from in front of the performance. The image placement is now set in stone. It’s rock solid, holographic, tangibly tactile. The dynamic range – both in an overall sense and in the subtler micro dynamics that so define the reality of natural sounds – is far superior.

The air within the room (studio) is clearer and sounds less opaque or ‘smoky’ (to be clear: it didn’t sound opaque or smoky to begin with, it’s just that when you do a direct comparison, that’s the sense you’re left with). The light is clearer and colours have more vibrancy. Perhaps the most notable difference of them all is how the gaps between notes seem clearer, more defined. As a result, the sense of timing, of real musicians with real feel, is more present and ‘live’.

What else? Well there’s more weight to the bass, and the cymbals have more shimmer. You can hear the extremities of the studio better too, which puts the performance in a more visual space. With vinyl (and I’m sure this is one of reasons why so many of us have come back to it as a format), you’re hearing the air and the ambiance of the studio or venue, making the soundstage akin to a window into the studio. This a neat transformative trick and one that delights audiophiles worldwide! In contrast, tape does a similar thing but it also pulls you as listener ‘into’ the soundstage. With vinyl, you’re looking through the window into a studio that’s outside of you, whereas with tape you’re right there inside the studio, in the club, in the recording – in the band, even! The players are maybe six or ten feet away from you, but they’re standing very really right here. They’re not miniature versions playing on a ‘smaller than life-size’ movie set, they’re life-size, and you’re right there with them. And not just them, but everything else too… the minutest shading of light and colour is just ‘there’, right in front of you.

A chat with Jerome Sabbagh

Since I’m always keen to find any excuse to talk tape with anyone and everyone, I set up a chat with Jerome Sabbagh to find out a bit more about Analog Tone Factory.

I ask Jerome when he became interested in audiophile sound quality and what was it that sparked his interest. It all harks back to 2004, he tells me, when he started recording under his own name and was keen to find his ‘sound’. The whole concept of sound became very important to him. He wanted the listener to be able to connect, and so began his quest to understand and find the best and most intimate sound he possibly could.

From there, we segue into a discussion about the term / notion of an ‘audiophile artist’. Jerome’s view on that is that while Analog Tone Factory could certainly be regarded as an audiophile-grade label, first and foremost the music itself has to stand up, and then immediately second to that, the skill, interpretation and energy of the performers must excite and enthral. The audiophile sound quality is perhaps the final piece to the puzzle, but in no way, shape or form should it dictate either the music or the performance. I couldn’t agree more with Jerome and on that one, and I can say with hand on heart that he and his label definitely don’t come anywhere near to the category of ‘hi-fi music’ or ‘audiophile music’ (i.e. music that has little or no appeal other than its sound quality).

Next up we get onto the topic of recording process (ever a source of fascination for me).

Basically, Jerome likes to play and record ‘live’ – meaning that he’s not wearing headphones in a sound booth listening to a drum track and trying to play along. He says (and again, we’re in total agreement here) that without the band playing together, there’s no band ‘dynamic’, and so that has to be artificially generated during the mixing process, at the point at which the various tracks (typically up to 24) are combined to make the ‘whole’. In contrast, by playing live the band actually does interact in real time, in the skin, so there’s a true band dynamic and energy which comes across in spades on any recording. In fact I’d add that the better quality the recording, the more you’re going to hear – and feel – that difference, hence the reason why so many analogue labels record in this way.

Jerome adds that his ideal scenario in terms of capturing the recording is to record direct to two-track tape. In other words he prefers not to record to multi-track, but instead for the ‘mix’ to be done live along with the players’ performance, which gives the most live and real recording of all. There are issues with this of course and it’s far from being the easy option, since whatever goes onto that two-track tape is the final and only result. You can’t go back in and make any useful edits or change the mix in anyway. Now, you could see this as a problem (or at least a challenge) but for my money, it’s precisely this that makes for a really exciting sound. You can feel the impact on the musicians and the performers – the fact that they have to get it right in one take. Again, when you’re dealing with high calibre artists, this will only elevate their performance, they’ll rise to the challenge and spar off each other to really give their best. And then there’s also the added benefit that, because you only go through the mixing desk (or board) once, the sound is better. In contrast, in a regular multi-track recording the sound goes through the mixing desk, to the multitrack recorder, then back through the board to the final mix (two-track) recorder.

Having said all that, the ‘Vintage’ album wasn’t actually done that way. It was recorded during the pandemic and, because of all of the restrictions that created, Jerome’s mix engineer James wasn’t available. So in this instance the performance (which was still ‘live’ with the whole band playing together – it was the later stages of the pandemic so thankfully they could), was recorded onto a Studer A800 multi-track recorder. It was then played back through the mixing desk for the final mix down to two-track tape.

Finally, the tape was sent to the great Bernie Grundman for mastering. Bernie cut the lacquer which was plated ready for pressing the vinyl editions. That same tape is the one that’s duplicated to produce the retail tapes: they’re direct 1:1 first generation copies of the original master.

A final word on this production

As mentioned just above, both the vinyl and the tape versions are made directly from the same master tape, with no additional eq. For the vinyl version, the master tape was played back on Bernie’s custom Studer A80 feeding his own custom tube cutting system. For the tape, that same master tape is duplicated by Jason Smith at Grey Matter Audio, played back on his Sony APR-5002 feeding via a Doshi tape amp, into a bank of Otari recorders.

Oh and another thing (okay, so that’s two final words), I have to say I really dig the physical presentation, the artwork, of this record and tape. To me it says ‘jazz’ ‘cool’ ‘art’ and ‘chic’…

All in all, this is a scintillatingly strong start from Jerome Sabbagh and his new label Analog Tone Factory. Here’s the link to their website where you can find out more and buy direct: www.analogtonefactory.com

And if you’ve an appetite for a little more rambling on the topic, here’s me on video doing just that.