This is the second of my Rhino High Fidelity Reel-To-Reel tape reviews, and this time it’s a band I’ve known and loved even longer than Yes – the subject of my first Rhino review. Here we have T. Rex’s Electric Warrior – widely considered to be Marc Bolan’s defining work.

This is the second of my Rhino High Fidelity Reel-To-Reel tape reviews, and this time it’s a band I’ve known and loved even longer than Yes – the subject of my first Rhino review. Here we have T. Rex’s Electric Warrior – widely considered to be Marc Bolan’s defining work.

Back in my Celestion sales repping days, I occasionally dabbled in what was then a novelty in the UK—karaoke. These days you won’t catch me anywhere near a microphone, but back then, with enough beer and the right mood, I could be persuaded to belt out a tune. My repertoire was small: a couple of Rolling Stones tracks, a couple of Peter Gabriel’s… but my go-to karaoke anthem was always T. Rex’s Get It On!

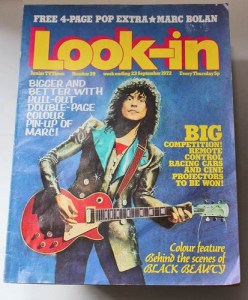

I’ve been a T. Rex fan since childhood—the kind of fan who cut out pictures from Look-In magazine and taped them to the bedroom wall. I still remember the thrill of seeing Marc Bolan host his own TV show, Marc. It only ran for six weeks before his tragic death, and I was just thirteen at the time.

I’ve been a T. Rex fan since childhood—the kind of fan who cut out pictures from Look-In magazine and taped them to the bedroom wall. I still remember the thrill of seeing Marc Bolan host his own TV show, Marc. It only ran for six weeks before his tragic death, and I was just thirteen at the time.

Over the years I’ve built up a modest collection of original T. Rex albums, including two UK pressings of Electric Warrior. Funny thing is, despite my lifelong admiration, I didn’t play them all that often. So when Rhino announced their first two reel-to-reel releases, the Yes tape was an instant “must-have,” while the T. Rex felt more like an “interesting choice.” Still, in the spirit of duty to my Reel-To-Reel Rambler readers—and with a nice little cost saving—I ordered both.

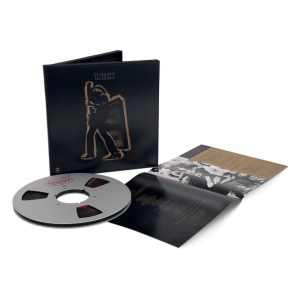

The unboxing

Just like with the Yes release, the outer packaging is a sturdy corrugated cardboard affair, smartly finished with Rhino tape branding. It’s clearly built to take a knock or two in transit, and sure enough, my tapes arrived in pristine condition.

The tape box itself is a beauty. Partial spot varnish on the front cover image makes the gold elements pop without going overboard. Honestly, it’s the nicest version of this iconic album cover I’ve ever seen.

Inside, you’ll find liner notes that include full-size reproductions of the original master tape box notes. These are fascinating to pore over—like peeking behind the curtain at the recording process.

The source

The Warner Brothers Records label makes it clear: this is the “Master” tape, intended for lacquer cutting only. That process usually involves tweaks—rolling off bass to keep the stylus in the groove, summing bass to mono, compressing dynamics, adding EQ to tame sibilance, and generally “polishing” the sound for mass appeal.

What’s more, as well as the tape notes stating that this tape is to be used for “LACQ Cut only” it also states “see EQ copy for tape copies”. This strongly suggests to me that this Rhino source tape is the actual ‘naked’ ‘raw’ master: the tape which is the closest record of the recording / mixing / production. It has none of the commercial compromises or ‘sonic make-up’ applied. I spoke with Rhino’s Steve Woolard (more on which below), he confirmed it: this is the exact tape sent from the UK to Warner in 1971, chosen specifically to give us the purest possible version. This decision I utterly applaud, this is what I want, this is the absolute. No watered-down commercial gloss, thank you very much.

The production: Recording The Masters

The duplication happens at Recording The Masters (RTM) in Avranches, France. I’ve visited RTM before (you can read my visit report here), but for this project I spoke with Iain Betson of UK-based Reel To Reel Resilience, who set up their duplication system.

Iain explained that RTM use a Studer A810 for playback of the source tape: in this case a flat 1:1 copy of the original master supplied by Rhino. The output of the A810 is fed into a distribution amplifier which facilitates direct in / out comparisons of any of the five connected Revox PR99 recorders (also supplied and set up by Iain). The whole system is fully balanced and allows for making five direct 1:1 copies at a time, each virtually indistinguishable from the supplied copy master.

The entire system was specified and supplied by Iain, except for the Studer A810 which RTM already owned along with a sixth PR99 which is ready set up and calibrated to perform as a drop-in replacement should any of the five recorders need substitution.

And to ensure consistency, RTM sends Steve Woolard three test copies—one from the start (‘copy zero’), one from the middle, and one from the end of the run. With only 500 copies produced, this process guarantees every tape is an equal and exact copy of the original master tape.

The tape stock

RTM uses their LPR 90 tape, which is basically their flagship SM900 formulation (a very high-level tape capable of recording beyond +9dB at studio levels, hence almost immune to overload and tape saturation) but on a thinner 1 mil backing (instead of 1.5 mil). The thinner tape means you get 48 minutes on a 10.5” reel instead of 33—enough to fit most albums on a single reel. That’s more cost effective, easier to store, and more convenient than flipping reels mid-album.

It’s worth noting that Horch House / Revox offer a similar choice between the standard and long play options, whereas Analogue Productions, The Tape Project, Hemiola etc. only offer the more expensive two-reel SM900 option. As neither my available shelf space nor money are limitless, I am entirely happy with the decision to go for LPR90!

To minimize production losses, Rhino makes two flat copies of the original master and sends both to RTM. Each copy only needs to produce 250 tapes, and with five recorders running, that means each master is played just 50 times. This, together with the fastidious checking going on, means that every one of the 500 copies produced should be virtually indistinguishable. I’m an extremely fussy customer and yet I have absolutely no qualms about what number copy I get. Sure, number one would be nice from a collectability perspective, but sonically, I really don’t care.

Listening to Electric Warrior

Alright, let’s get down to business. I’ve unboxed my precious new tape, popped it (tails out) onto the recorder, and hit rewind. One quick note before we dive in: the red leader tape is long. Unusually long, in fact—and that’s a good thing. It makes rewinding a breeze without worrying about the leader flying off the reel. Big thumbs up to Recording The Masters for that thoughtful touch.

Before pressing play, here’s another detail worth mentioning: Rhino’s Reel-to-Reel tapes are duplicated at 320nWb/m which is absolutely ideal. 320nWb/m is the most commonly used studio standard worldwide and is also the level used by most ‘master copy’ tape labels, so for replaying ‘master copies’ from any of the growing number of tape labels, simply set your machine up for 320nWb/m CCIR replay (or get your tech to do it) and then forget about it.

Now we can hit that play button…

As the opening beats of Mambo Sun thunder from the speakers you’re left in no doubt that you are witnessing something you’ll have never heard before. There’s an immediacy, a weight, and power that you simply can’t cut into vinyl, nor capture with any level of digital sampling. It is exactly like being in the studio; what you are playing is an exact copy, of a copy, of the tape created by Tony Visconti in that studio all those years ago.

In my setup—a Studer A80 once owned by EMI, paired with full-range Kerr Acoustic studio monitors in a carefully treated room—the sound is pure studio quality. Honestly, I don’t think it gets better than this.

For comparison, I lined up my UK original vinyl pressings against the Qobuz stream. Electric Warrior is a phenomenal album either way, packed with classics like Jeepster, Get It On, Cosmic Dancer, and Life’s A Gas, plus some gorgeous deep cuts. Both the LP and stream sound great (the LP especially), but neither comes close to the Rhino tape.

By comparison both the LP and streamed versions exhibit a ‘forcedness’: ultimately, they’ve been skilfully mastered for their respective mediums which inevitably involves compromise. Some listeners of course might actually like this: nearly all modern music is compressed to hell meaning that everything appears “loud”; there are practically no dynamics, no natural textures, no real space. Natural feeling, the swing, groove and musical interplay are pretty much lost in a void. By contrast, the Rhino Reel To Reel tape provides an insight into the recording that you simply will never have experienced before. It is on another planet: you almost don’t need to ‘listen’ to this tape; you simply ‘hear’ it. Everything is just there, everything just ‘is’. There is no forcing of the bass, Marc’s vocal, or the guitar. Everything breathes with a natural air. It is spine-tinglingly sublime.

Flo and Eddie’s backing vocals, Marc’s searing guitar work, the background orchestration and of course, the pumping beats of the bass, drum kit and Steve Took’s deft percussion work; everything entwines in believable space, is musically captivating, and sounds unnervingly real. There’s a natural propulsive reality to the sound (just as with The Yes Album) that far exceeds the pseudo-impressive mastering tricks used to make LPs playable and sound ‘loud’.

I have now listened to this amazing tape over and over again, and what you get is far closer to the actual recording than anything ever released before now. Marc’s voice is as solid as a rock, but it’s not ‘in your face’: it isn’t right at the front of the soundstage, Marc’s guitars (he plays all the guitar parts, often two and sometimes I suspect three), are positioned right at the front of the soundstage, about waist height, sometimes on the left, sometimes on the right, and sometimes dead centre (depending on where the producer – Tony Visconti – decides to place the instrument in the mix). Meanwhile Marc’s voice comes from about 5 feet above the ground (in my system) and perhaps a foot or so further back in the soundstage than the guitars. Think about it, the reality of this is spot-on. Marc stood around five feet four inches tall and he didn’t play his guitar behind his back. This is staggeringly real!

Getting back to Marc’s voice: it’s soft, it always was, and the tape reveals this in beautiful reality. Does ‘soft’ sound weak or distant? Nope, it sounds absolutely natural, explicitly real, and at times even sensuous: almost like he’s whispering softly in your ear.

T Rex were very much a beat driven group, don’t forget for a while they were a duo, just guitar and percussion, then a full band but a band backing up the two ‘key’ elements of Bolan’s guitars (and voice), and Took’s percussion. So of course, the beats are heaviest in the mix and literally propel this album forward. The drums are phenomenal. The weight and slam of the kick drum, and the snap and rattle of the snare are startling: there is no vinyl LP, no CD, no high-resolution stream that comes anywhere even remotely close to this level of reality. And when we get to the less forward elements: the orchestration for example; those strings just sound real. Back then in 1971 they didn’t have sampling, this is real music, played by real musicians and even the mixing and production required artistry. There were no plugs-ins, no magic buttons to snap everything into focus, no AI, no cut-and-paste fakery, just pure honest skill, and natural artistic expression. Halleluiah!

Final thoughts

This release is nothing short of incredible. I’m thrilled Rhino has joined the “tape party,” because the possibilities for future titles are endless. I’ve got four months to save for the next one, and whatever it is, I’ll be first in line. Eyes wide open, ears ready. Watch this space.

To find out more and order a copy, head over to the Rhino Store: https://store.rhino.com/products/electric-warrior-rhino-high-fidelity-r2r

If you’ve a taste for more rambling on this one, here’s my video review…

Interview with Steve Woolard

…and here’s the above-mentioned interview with Steve Woolard