There’s a history lesson in music, sociology and economics in open-reel tape. Ken Kessler takes us on a tour.

Musing about reel-to-reel users of the Golden Age of Pre-Recorded Tapes, based on the evidence provided by the 2,200+ tapes I’ve acquired, I stand confused. The dichotomy between skilled enthusiasts and clumsy oafs is, I suppose, no different than today’s LP arrivistes, who call them “vinyls” and probably don’t realise that the £99 USB-equipped turntables they bought are chewing the bejeezus out of the LPs they just acquired for upwards of twenty quid. You wouldn’t believe the state of some of the tapes I’ve acquired from the USA….

“a luxury pursuit”

Back on this side of the Pond, and without giving you a condensed history of the British economy in the decade-and-a-half following the Second World War, let’s just say that open-reel tape – due to both the cost of hardware and the tapes themselves – was a luxury pursuit for the British, slightly less so for Americans. I dug into the earliest Hi-Fi Yearbooks, checked out the prices, converted them to current values and then looked at the median wages and disposable income of the same years and now I wonder: who in the UK in the 1950s and early 1960s, aside from solicitors, politicians, and criminals, could afford anything?

Again, I’m reminded of my own, earliest exposure to open-reel tape, when my father spent many hours in the Eisenhower years recording his LPs (who cared about copyright before cassettes made it an issue?) to swap with enthusiasts in England. When I emigrated to the UK in the early 1970s and caught up with all the post-war history I should have paid attention to in school, friends merely confirmed what my father’s activities illustrated: any form of hi-fi enthusiasm was a luxury pursuit, and if you were on a first-name basis with Thomas Heinitz, you probably parked your Bentley in Mayfair.

“obsessed with export”

This still doesn’t explain the cause of my confusion, other than acknowledging that Great Britain PLC was obsessed with export, necessary for rebuilding the economy during and just after the years of austerity and rationing. Indeed, when I interviewed Raymond Cooke (KEF), Peter Walker (Quad) and Alastair Robertson-Aikman (SME) more than 20 years ago, each stressed the importance of foreign markets, which justified why British manufacturers, who rivaled the best that the USA and Germany could come up with when it came to hi-fi, had limited activity in their home markets.

Let’s not paint too gloomy a picture. All of them had healthy sales here, e.g. Quad sold a “shitload” of Quad IIs and 33/303s and 405s and ESL57s and ESL63s in this country, and you probably can’t count the number of KEF 104ABs or SME 3009s that stayed in Great Britain. But make no mistake: separates hi-fi was a rich person’s game in the years before Japanese brands brought prices down to an affordable entry level, and the hi-fi-as-an-elite-hobby period corresponds EXACTLY with the years when pre-recorded open-reel tapes were viable.

What struck me as important is the need (if history is your thing) to contrast the US and the UK markets at the time. I say this because British hi-fi enthusiasts were among the most committed and knowledgeable, yet hamstrung by limited disposable income, while Americans had the passion, the home-grown hardware AND the money. I mention only these two territories because I can find little or no evidence of other markets producing pre-recorded open-reel tapes, even when as committed to both hardware and blank tape manufacture as Germany, where the format was invented.

“Japanese labels did two things right”

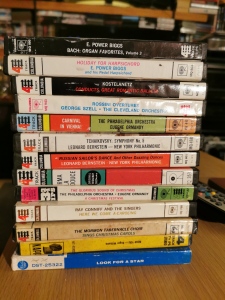

As for Japan, there were pre-recorded open reel tapes back in the day, and I’m lucky to own a couple. It was dear, departed Tim de Paravicini who explained to me the geographical component to the genre, vis-à-vis US, UK and Japanese tapes. While I have no idea how many titles were issued in Japan, Tim did explain that jazz was predominant, the tapes were hugely expensive, the Japanese had post-war challenges like the UK’s with which to contend, but crucially, Japanese labels did two things right: the first was that the chosen tape stock was top grade, and the second was duplication in real-time, that is 1:1.

Right until the end, Tim was buying up whatever Japanese tapes he could find, including amazing demo tapes on 10in spools from the likes of TEAC, while he cherished the 7½ips ¼-track tapes form the regular labels, e.g. titles from Frank Sinatra, Miles Davis, and Ramsey Lewis. I am lucky to have US copies in the same format as my two Japanese tapes – the soundtrack to South Pacific and a Percy Faith album – and can confirm hands down that the Japanese copies better the U.S. copies (which are still unbelievable by any standard that applies to LPs) in every way.

Back in the USA

As for US-made pre-recorded open-reel tapes, Tim told me that the American tapes sound so good, despite high-speed duplication, because the companies which made the copies (Ampex, Bel Canto, etc) were scrupulous in maintaining the tape decks’ set-ups, adjustments and maintenance. Whatever the reason, I can count less than a dozen tapes out of the 700 I’ve now tested which don’t sound too hot, and this has nothing to do with the tapes’ condition. In essence, they sound naff because they were on budget labels, poorly recorded, or on mediocre stock.

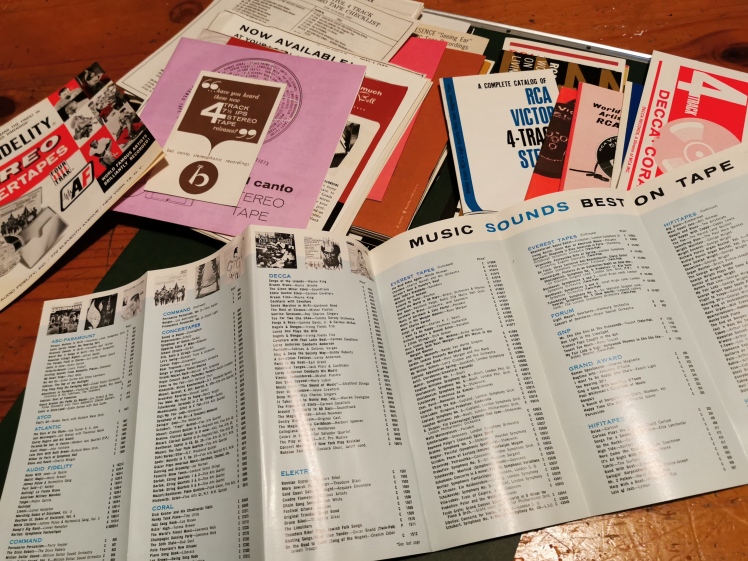

This brings us to the most important aspect of American pre-recorded tapes: the sheer scale of the market. As best as I can estimate using a stack of catalogues I’ve acquired, there must’ve been in excess of 10,000 titles in total. Just one catalogue – CBS from February 1964 – lists around 400 titles. From the same time, Bel Canto’s covered a huge variety of brands (but not including the three biggest – Capitol, RCA and CBS), and theirs contained something like 750. Then add 500 or so from RCA, and 300 from Capitol. Remember, this was 20 years before the last pre-recorded open-reel tape was issued by the major labels, and aside from a bunch of Elvis Presley tapes there’s hardly any rock music in the mix.

With US labels far and away the dominant source for pre-recorded open-reel tapes, starting around 1953/4 with both tiny, esoteric specialists issuing mono tapes, EMI in the UK launching theirs, and major US labels supporting the format on the eve of the LP’s arrival, the configurations the American companies offered reveal both the evolution of pre-recorded tapes and the venality of the music industry. Let’s dispense with the latter first.

Diminishing returns

If you compare any of the tapes up to around 1958-9 to the last ones made circa 1984, you’ll see how the record companies cheapened what always was a premium format. This was industrial-strength corporate stupidity, the sheer cupidity of the record companies blinding them to an obvious reality: that US open-reel tape buyers were audiophiles with expensive gear who were prepared to pay as much as $12.95 in 1960 for a single open-reel tape. In 2021 values? That’s $120 in today’s money, around the price of a Mobile Fidelity One-Step, but less than any of the current 15ips open-reel tapes currently being produced.

You would’ve thought that the record labels would’ve handled this luxury sector cash cow the way the Japanese treat their Wagyo steers. No way. The tape boxes went from thick card with cloth-reinforced spines to thin card and spines that swiftly tore. The plastic spools grew increasing thinner. Most tapes came without leader tape or tail. Talk about cheapskates. But what was worse was how these cost-cutting manoeuvres tracked (pun intended) the way tape itself was evolving.

As decks improved, and that covers everything from the quietness of solid-state circuitry over tubes (which even I, a valve nut, have to admit) to better head materials such as ferrite or glass or permalloy, to superior tape formulae, the record labels found ways to give less for more. The first move was from ½- to ¼-track, which halved the amount of tape need for an album. The second was to produce tapes at 3¾ips instead of 7½ips, halving the tape quantity once more. For the most part, labels did distinguish between the formats according to a scale of retail prices, but overall, corners were cut.

I actually have one or two tapes which were issued in both ½-track and ¼-track formats, and in 3¾ips and 7½ips. Don’t let any oily record label bean-counter tell you there’s no sonic difference. Which brings us to where I got started on my return to tape: after the idiots at Capitol realised that the Beatles were the biggest act (and biggest earner) in musical history, they deleted the inferior, 2-on-1, 3¾ips tapes and reissued them at 7½ips. Which is how Tim de Paravicini got me hooked on open reel, with a 7½ips ‘blue box’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Now, commercial pre-recorded tape has been dead for more than 35 years. You just gotta grin and bear it.

After working as Assistant Editor for the short-lived Stereo – The Magazine, Ken Kessler joined Hi-Fi News & Record Review in 1983, where he still serves, latterly as Senior Contributor. He writes a monthly column for SoundStage and contributes as well to online magazines Tone and Copper. A collector of old hi-fi components with a passion for the history of audio, Ken is the author of Quad: The Closest Approach, McIntosh… For The Love Of Music, and Audio Research – Making the Music Glow, and is co-author of Sound Bites: 50 Years of Hi-Fi News and KEF: 50 Years of Innovation In Sound. He is currently working on another four audio histories.