If you want the short version of this review, minus my ramblings, here it is: three sonatas, three passionate fanatics, three steps to heaven! For a bit more detail, read on…

‘Lost in music’

I often ramble on about ‘audiophile recordings’ across multiple media, not just tape, and sometimes in a non-too effusive light. By definition, these recordings are trying to capture – or retain – something that’s commonly lost in your standard musical recordings.

The ‘something’ in question might have been deliberately thrown out, or perhaps not even captured in the first place, in the process of creating a recording deemed suitable for general release i.e. one that’s balanced, even, not too challenging and offers a pleasing experience.

If you detect a tone of ‘meh’ in those words, then you’re not too wide of the mark, though I’m certainly not deriding the recording industries we all know and love! And yet, at the same time, I can’t help but feel that what the 21st century listener is presented with – even in many ‘audiophile’ releases – is all-too-often a ‘perfected’ thing: edited, massaged or just plain ‘corrected’ to suit the masses until we’re left with something that’s a long shot from authenticity, art or unbridled passion. The thing is, ‘the masses’ don’t actually exist. All experience, even shared experience, is lived individually (in terms of music or indeed anything else) and so catering to a presumed ‘mass’ taste doesn’t really cater to anyone’s as such.

So what’s my point, I hear you ask. Well let’s flip over to the opposite pole, which in this case is represented by Canada-based UltraAnalogue Recordings and by Ed Pong, the spirit behind the company and one of the aforementioned ‘passionate fanatics’ (the other two being pianist Vadym Kholodenko and composer Beethoven).

‘Ultra’ by name and by nature

Ed is a retired dentist, music lover and audiophile. His musical passions lie entirely within the classical domain, and his love of audio stems back to the ‘golden age’ of the 1940s / 1950s. I’ve already given you a run-down of Ed’s recording and playback system in a number of earlier reviews, but let’s kick off here with a recap.

His microphones are a matched pair of vintage Royer 122v ribbons, which offer an unparalleled lush richness, depth and detail. These are positioned around ten feet from the piano, in order to capture the natural ambience of the space. The space in question is Ed’s own concert hall, which – somewhat randomly – also doubles as an indoor swimming pool (covered, obviously, during performances and recordings). While this might sound initially alarming, the sonic signature is one of lushness, dripping with natural reverb, but brightly lit – like a magnifying glass on the overall package, capturing the dynamism and immediacy and blowing it up large. I’m not suggesting that the swimming pool is the essential ingredient here, rather it’s about the whole dynamic envelope: what happens when you put a concert grand into a room and let a world class pianist express his interpretation of three of the most emotionally and intellectually challenging compositions ever created.

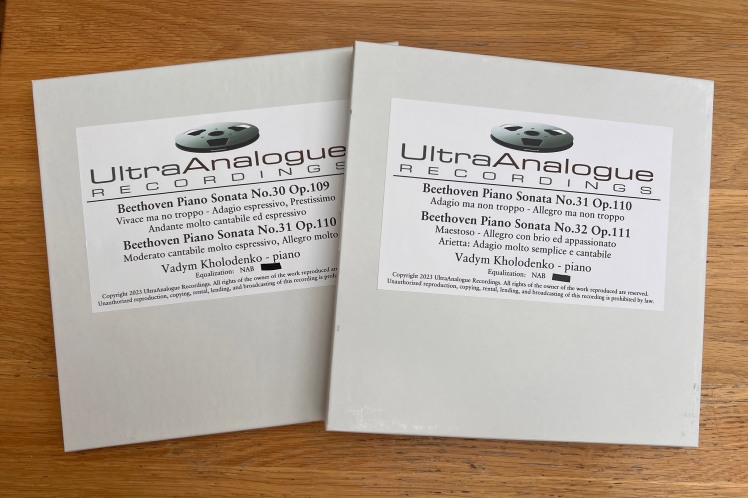

Which brings me (in my usual rambling fashion) to the particular subject of this review, which is Pong’s recording of Beethoven Piano Sonatas Numbers 30 (opus 109), 31 (opus 110) and 32 (Opus 111), performed by pianist Vadym Kholodenko.

These three Sonatas were written very near to the end of Beethoven’s brief life, by which point he was already profoundly deaf and composing ‘on instinct’ if you like. To my mind (and ears), his connection to the muse, the soul of the world, the universe, God – whatever you want to call it – was at its height.

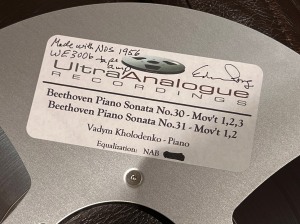

But before we get too lofty, let’s get back to the system: those exquisite Royer ribbons are wired with pure silver wiring to Ed’s bespoke microphone preamp, which itself was designed exclusively for Ed using NOS (new old stock) Western Electric WE437a & WE300b tubes. Those tubes are so rare it could be fair to call them fabled. The wiring, and transformers within the preamps, are all pure silver. No expense has been spared and no veils are present, the essence of this set-up is vivid purity. The mic preamp feeds one of Ed’s Studer A80 master recorders, and even these beautiful machines aren’t left ‘as is’. Again, all of the wiring is pure silver, the power supplies are separate and bespoke, and they use batteries for utmost purity.

The next step in the chain is of course the playback, and this has recently reached a new pinnacle. It has always been valve based, silver wired etc, but now Ed has added a new toy: a tape amplifier built using those fabled WE300bs. The sound of these vintage direct-heated triodes gives a vivid natural full-bodiedness that defies description. Where these go in the signal path is on the tape head output, so every tape that Ed produces from now on is replayed through this tape output circuitry and recorded onto a second (battery powered, silver wired, valve-based) Studer A80. Nice!

The resulting impact

The result is extreme, immediate, vivid realism. Not the kind of ‘realism’ you’d hear on a commercial recording, so not plastic, constrained, polished or packaged for consumption. Rather, this is like a shot of utter gut-hitting being-there-ness, straight into the jugular.

When the first notes ring out, you will more than likely be quite taken aback. This is dynamic in a way you won’t be used to. On modest systems you may well run into clipping and hardness, but as you acclimatize you realize just how real this feels. It’s not so much a sound as an entire sensation: the ease with which you hear every single finger and foot movement; every single note is apparent, including how loudly each individual note is played (the difference of soft to loud is startling, truly startling). Listeners to pretty much anything commercially produced will not have heard anything like this. But if you’ve ever been in a room with a full size concert grand, and have sat yourself about ten feet away while a world class pianist ‘lets rip’, then you’ll fully appreciate how bang-on the effect is here. There’s no production, no editing, no mastering, no limiting, no compression, no EQ. What you hear is what those Royers produce, placed in the sweet spot, which is what Ed feels best captures the experience of being there. You really do hear every single note: when the key is pressed, when it’s released, when dampers are engaged. And if you think that sounds analytical, think again. The effect takes you totally into the feeling realm: you ‘feel into’ every note as if searching tentatively for the space in which to end one note and hand over to the next, or whether to sustain and blend in with the next note. It’s almost as if you become the listener, the pianist, the instrument and the notes, all as one. This is Beethoven’s compositional genius in full flight, being ‘read’ by a true artist, and being captured, vividly, entirely, for what it is. What it is, is incredible.

Interestingly, a friend called me while I was listening and I took the call before pressing pause on the hi-fi. His first words were, “Where the heck are you, what are you doing??”. He could hear a grand piano ‘giving it some’ and assumed I was out at some kind of event. This is a guy who is an audiophile par excellence, a professional hi-fi reviewer by trade, and yet even with all of the limitations of a pair of mobile phones between us, he mistook the reality of this recording for reality itself.

I’ve got to be honest, it wasn’t what I expected of this tape. I mean, all those vintage tubes, all of that silver wiring in Ed’s set-up… wouldn’t that make for a euphonic sound, all warm and cuddly, not pin-sharp faithful and crystal clear?

Well, no. Modern hi-fi recording technologies do a lot of things, but they also lose a lot. I’ve amazed many folks over the years by playing them shellac 78s on acoustic equipment (by which I mean wind-up gramophones). There’s an immediacy that very few of even the most high-end systems can’t get close to. Of course there also are very many limitations, but it’s what gets lost that has always intrigued me and so I will often play some such thing for the occasional visiting hi-fi designer (I guess in the hope that someone, someday will work out unequivocally how to put it back in!). Sadly there’s an inevitable squashing and smoothing that goes on with most electronic circuits, and the more complex the circuitry, the greater this effect, and yet what gets lost is oh-so-critical to the real live experience.

I still remember once hearing a stunning-sounding system in this respect. It comprised a small triode amplifier feeding a pair of massive Lowther Voigt Corner Horns. Again, there were many aspects you could criticize but it had something very, very real, something that sounded utterly alive.

As an aside while on the subject of sound, a few years ago Ed Pong and I were having a debate / discussion about NAB versus CCIR EQ. I was intrigued and so Ed made me two versions of a tape, one NAB and one CCIR. The arguments for these two standards basically boils down to noise: CCIR boosts treble on recording, thus reducing tape hiss by the required treble cut on playback. This makes sense and in the majority of studios in these digital days CCIR is used. Anyway, I preferred the NAB tape, especially with Ed’s recording set-up and how he likes to push the envelope. I found the CCIR tape slightly more hard and glassy whereas the NAB one still had all that treble energy but kept it soft and luscious, albeit with a crashingly immense power.

As an aside while on the subject of sound, a few years ago Ed Pong and I were having a debate / discussion about NAB versus CCIR EQ. I was intrigued and so Ed made me two versions of a tape, one NAB and one CCIR. The arguments for these two standards basically boils down to noise: CCIR boosts treble on recording, thus reducing tape hiss by the required treble cut on playback. This makes sense and in the majority of studios in these digital days CCIR is used. Anyway, I preferred the NAB tape, especially with Ed’s recording set-up and how he likes to push the envelope. I found the CCIR tape slightly more hard and glassy whereas the NAB one still had all that treble energy but kept it soft and luscious, albeit with a crashingly immense power.

Beethoven’s final sonatas

I can’t read music, I’m not a music critic and so I can only legitimately report my personal experience here. These sonatas are, in a word, intense. In two words, intensely involving. So much so that, on first listen, I was slightly overwhelmed by the sonic fireworks, the immense scale and the complexity of composition. Initially, it was all a bit much. On second listen I was more acclimatized but not yet fully sucked in. On the third listen, I got it, or perhaps I’d be better saying that it got me.

As I’ve already discussed, the sound is so vivid that you follow every single note: the attack, the scale, the decay and the transition into the next note, or into space and silence as the decay fades or is cut short by Vadym. The music ebbs and flows like a river, sometimes soft and feminine, nurturing, sometimes powerful and masculine; sometimes it’s tentative and searching, other times confident and dancing – from a crashing crescendo to the final ‘stop’ as Vadym damps the last decaying note. On which note…

Pianist Vadym Kholodenko

Ukranian Vadym Kholodenko is a multi-award winning pianist and Gold Medallist of the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. He has performed with many of the world’s leading orchestras in Europe, North America and Asia, and his recordings have received accolades including BBC Music Magazine’s Editor’s Choice Award the much-coveted Diapason d’Or de l’Année. Critical reviews describe his artistry as “truly outstanding” (Gramophone Magazine), “carefully contoured and impactful” (BBC Music Magazine), and “playing that pulls no punches: Kholodenko is in the elite of classical pianists” (Norman Lebrecht, for The Critic).

What makes him ‘fanatical’? Well, in addition to the pursuit of his art to the highest degree in performance, there’s also an obvious commitment to excellence in sound recording. To put it bluntly, his ongoing work with UltraAnalogue Recordings is hardly a commercial decision, insofar as it’s not something that comes with a big pay packet (newsflash: nobody making superb quality tapes is making a fortune, these are passion projects). No doubt conscious of Vadym’s considerable profile, Ed Pong did mention to me that he was considering putting this recording out on vinyl to enable a wider audience to hear it. Which I have to say made me laugh (sorry Ed), since I had written in my listening notes that this experience is so far from the norm that I couldn’t possibly imagine how a playable vinyl LP could be made – the stylus would likely be ripped from the cantilever, or the cantilever from it’s suspension! Of course it could be put onto vinyl, but not without production and mastering for that purpose which, to my mind, would risk losing what makes it so incredibly special.

Final words

To sum up, listening to these two tapes has been quite a journey. Beethoven was certainly a powerful force, especially at this climax of his creativity; Vadym Kholodenko has embraced this and dived headlong into the challenge of it, and Ed Pong has masterfully captured it. Taking no prisoners, this is the work of three passions, beautifully converging to create something truly remarkable.

Here’s where you’ll find it: https://ultraanaloguerecordings.com/new/shop/tapes/musician/vadym-kholodenko/beethoven-piano-sonatas-no-303132-op-109110111/